The world’s oldest known wooden tools, used some 430,000 years ago, were discovered in Megalopolis, Arcadia, by an international team of researchers from Germany, the United Kingdom, and Greece. “This area was very important for human evolution throughout Europe,” emphasizes to APE-MPE the Greek head of the research, paleoanthropologist Katerina Harvati.

The finds come from the archaeological site Marathousa 1, which dates to the Lower Paleolithic period—a period that began around 2.5 million years ago, lasted until approximately 300,000 BC, and was characterized by the emergence of early humans (hominins) and the first tools.

Excavations in the Megalopolis area have been long-term, from 2013—when the Marathousa 1 site was discovered during a surface survey—until 2019, when systematic excavation ceased. During the excavation, stone and bone artifacts were found, that is, objects that had been processed by humans, as well as mammal bones. However, the researchers’ interest was also drawn to something even rarer: wooden finds, which were studied in detail.

Small wooden tool, the possible use of which is not known

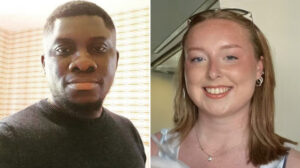

In a scientific article, led by Professor Katerina Harvati, Director of the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen, and Dr. Annemieke Milks of the University of Reading, published in the journal PNAS, the study of 144 wooden finds from the 2015–2019 excavation period is presented.

From this study it emerged with certainty that two of the finds are wooden tools. One is a piece of a small alder trunk, stick-like in form, which bears clear signs of processing and use and was most likely used for digging along the lake’s banks or for removing tree bark.

The second is a very small piece of wood from willow or poplar, which also shows signs of processing and possible signs of use. This find represents a previously unknown type of tool, and researchers have not yet reached conclusions regarding its use. “This tool broadens our horizons and our knowledge of the technology used to create tools,” emphasizes to APE-MPE the head of the study, Katerina Harvati, a leading expert in human evolution.

A third find mentioned in the publication—a larger piece of alder trunk with deep grooves—appears to have been shaped by a large carnivorous animal, possibly a bear, rather than by humans, according to the researchers. In addition, five other finds are presented that may constitute artifacts; however, further study is required to reach a secure conclusion.

Digging or multifunctional stick

Unique conditions for the preservation of wooden objects

The site dates to 430,000 years before present; therefore, these finds are the oldest wooden artifacts ever discovered, pushing back the dating of the use of this type of tool by at least 40,000 years. As researchers note, the previously known oldest wooden tools come from the United Kingdom, Zambia, Germany, and China and include spears, digging sticks, and tool handles. However, all are more recent than the finds from Marathousa 1. The only older evidence of wood use comes from the Kalambo Falls site in Zambia, dating to approximately 476,000 years ago. However, this was not used as a tool, but as a construction material.

Marathousa has unique conditions for the preservation of such organic finds. In the Marathousa area there was a lake—sometimes deeper, sometimes shallower—for hundreds of thousands of years during the Lower Paleolithic period. “The finds were buried very quickly along the lake’s shores or under shallow water, ideal conditions to prevent organic materials from decaying or decomposing,” explains Ms. Harvati.

Since the discovery of wooden objects and other finds made of organic material is rare due to their fragile nature, and the relevant literature is therefore limited, their study is carried out by scientists specializing in wood and other organic substances.

“We carefully examined all the wooden finds, observing their surfaces under the microscope. We found cut marks and incisions on two objects—clear indications that they had been shaped by early humans,” notes Dr. Annemieke Milks of the University of Reading, a specialist in early wooden tools.

The study of the finds, conducted at the laboratory of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, used powerful microscopes and computed tomography in order to determine whether their processing was human-made. In addition, since these objects are very fragile, their preservation in the laboratory took place under special conditions, inside plastic bags with distilled water, stored in a refrigerator.

Refuge area

At Marathousa 1, more than 2,000 stone and bone artifacts have also been found, highlighting the skill and varied activities of the people who once lived there. The tools—stone, bone, and wooden—and the skeletal remains of elephants and other animals found at the site indicate that the location, once situated on the shore of the Pleistocene lake of Megalopolis, was used by Paleolithic humans for animal butchering around 430,000 years ago.

It was the Middle Pleistocene period (which overall lasted from approximately 774,000 to 129,000 years ago), “a critical phase in human evolution, during which more complex behaviors developed. The first reliable evidence for targeted technological use of wood dates to this period,” describes Ms. Harvati to APE-MPE.

Through the study of the organic and other elements preserved at the site, researchers attempt to reconstruct the climatic conditions that prevailed in the area, in order to draw conclusions about the climate, environment, and life at Marathousa 1. “Humans were there during a glacial period, so conditions were cold. This indicates a quite significant role of this site, and more broadly of the Megalopolis basin, as a refuge for animal populations, humans, and plants under these very harsh glacial conditions. At the same time, habitation in central and northern Europe would have been extremely difficult or impossible. This shows us how important this area was for human evolution in Europe,” emphasizes Ms. Harvati.

The study involved researchers from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the Ministry of Culture, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, and the University of Ioannina. The research is funded by the European Research Council and the German Research Foundation.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions