An instinctive remark by Pavlos De Grece—the six words “many things cross my mind”—was enough to cause overexcitement, even palpitations depending on one’s hopes or fears, on the Greek political scene.

To a certain extent, understandably so, since “many things cross my mind,” in the context of a wide-ranging interview by the one-time “Crown Prince,” can only mean that Pavlos is indeed considering the possibility of becoming involved in public affairs in Greece—at least initially.

Naturally, he would be seeking a role as a regulator of developments—if not a leading figure. From this perspective, both the interview itself and its timing—his television appearance—could be seen as a discreet but meaningful prelude to an upcoming electoral period, however that may be defined.

The example of Simeon II

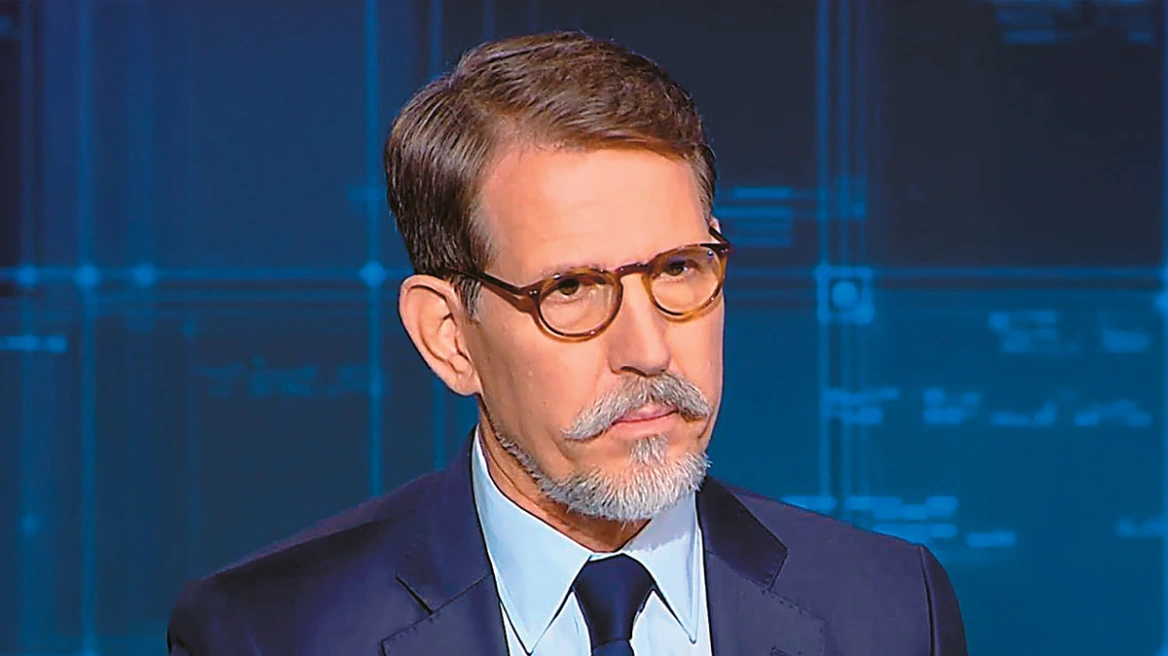

The much-anticipated question in his 90-minute interview on ANT1, to which Pavlos De Grec responded with the above cryptic phrase, concerned whether he would consider following the example of Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. That is, a former monarch who, more than half a century after the abolition of the monarchy in Bulgaria, decided to seek voters’ trust as an ordinary politician rather than as a hereditary sovereign.

Simeon ultimately won Bulgaria’s 2001 elections and became prime minister, adding that title to his former one as king. Since Simeon is related to Pavlos—as are the royal houses of Denmark, Spain, Great Britain, and others—Pavlos could in theory draw inspiration from him.

“Politics does not interest me”

However, listening more carefully to what Pavlos De Grec told journalist Nikos Hatzinikolaou, the phrase “many things cross my mind” does not necessarily include any concrete plan to enter Greek politics. On the contrary, he essentially ruled out such a prospect, stating clearly that he is not a politician, regardless of whether “politics is in my blood,” as he put it.

“No, I am not interested in politics. What interests me is being useful and doing something good for my homeland. My relationships with other countries are very strong, with companies, with people from various fields, who could be useful to Greece. So if there is a way for me to help them support our country, of course I will do it.”

His statement likely disappointed those who harbored nostalgic hopes of a quasi-restoration of the monarchy. Pavlos emphasized that the calendar reads 2026—not 1920. He said he is happy that he and his family finally have legal identification, are no longer considered stateless, and that democracy and the constitution in Greece are solid and unshakable.

He also noted that in about a year and a half, enjoying full Greek citizenship, he will be able for the first time to exercise his right to vote in his birthplace—the country he has chosen to live in and regard as his homeland.

Pavlos’ Project

Focusing exclusively on whether Pavlos will form a political party or cooperate with existing ones may overshadow the real news from his interview: his ambition to create in Greece an organization to support youth entrepreneurship, closely linked to national efforts to reverse brain drain and encourage the return of economic migrants.

The body he envisions appears partly modeled on the The King’s Trust International, founded by Charles III. Pavlos has direct experience with its operations, having served as its president from 2016 to 2022 and currently as vice president.

With a mission to combat youth unemployment and support business initiatives, the King’s Trust International says it has helped around 100,000 young people since 2015 in Britain and 20 other countries. A Greek-adapted version could demonstrate that Pavlos is not merely dreaming but implementing ideas for the benefit of fellow citizens, leveraging his global network among influential elites—including business magnates and members of royal families, many related to the De Grec family.

However, Pavlos did not clarify how, when, or with whom he intends to establish such a fund. He expressed his intentions more as an idealized aspiration than as a structured, concrete project.

Constantine’s mistakes and defending his legacy

A sense of bitterness about the past occasionally appears in Pavlos’ words—but mostly as something he tries to refute. He seeks to counter the impression that the former royal family remained stuck in resentment toward the Greek state.

His message is essentially “let bygones be bygones” regarding the years when the family (then known as Glücksburg) was considered unwelcome in Greece, allowed only a few hours to attend Queen Frederica’s funeral, and engaged in legal battles over royal property.

Yet a degree of royal ressentiment remains, especially in defense of his father, Constantine II of Greece. Pavlos is convinced that:

a) His father could not have done more to resist the April 21, 1967 junta, and

b) Konstantinos Karamanlis broke a promise in 1974 regarding his restoration to the throne.

These points remain longstanding criticisms of Constantine’s political judgment, despite what many consider serious missteps during his reign.

“All comes down to ‘if,’” Pavlos said. If his father had not been so young in 1967, if tanks had not surrounded Tatoi, if communications had functioned, things might have been different. He stressed that Constantine was alone, with only his pregnant wife beside him, and that he later attempted a counter-coup against the junta.

Regarding his father’s failure to return after democracy was restored, Pavlos placed responsibility squarely on Karamanlis, whom he referred to only as “a gentleman” and “a personality,” avoiding even naming him directly. Though painful and unjust in his view, he insists the family has now moved on.

Sofia’s return and Irene’s “reincarnation”

About a month ago, in deep mourning for Princess Irene, Queen Sofía of Spain came to Athens and will return again for the 40-day memorial service. A symbolic dimension has emerged from Princess Irene’s death and the prominence of Irene Urdangarin, now tenth in line to the Spanish throne.

After Princess Irene’s passing, Irene Urdangarin appears to have filled the emotional void for Queen Sofía. The 20-year-old is one of Sofía’s eight grandchildren from her estranged husband, Juan Carlos I.

Although the will has not been opened, Irene Urdangarin is reportedly the principal heir to Princess Irene’s estate. Princess Irene, who never married and had no children, is said to have left her belongings primarily to her namesake grandniece.

The Spanish throne

Speculation in Spain has focused on why Princess Irene’s estate did not pass to the obvious heirs of the royal house—Princess Leonor and Infanta Sofía, daughters of King Felipe and Queen Letizia. The current monarch is Felipe VI.

Rather, in keeping with her lifelong nonconformism, Princess Irene reportedly entrusted her estate to the four children of Infanta Cristina—especially to Irene Urdangarin.

Irene Urdangarin has kept a low profile, participating in humanitarian missions in Cambodia and supporting children with special needs. She herself is dyslexic, a struggle she has faced since childhood. Her father, Iñaki Urdangarin, recently praised her as a “heroine” in his autobiography.

In her own way, she is emerging as an unexpected contrast to Leonor, Princess of Asturias, who is being systematically prepared to succeed her father on the Spanish throne when the time comes.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions