Saint Augustine’s saying, “If you do not believe, you will not understand,” perfectly fits the life and work of Hatzi-George the Athonite and Hieromonk Tychon the Athonite. These are two ascetic figures of the Church who dedicated their lives to God and their faith, and who were canonized yesterday by the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

The Holy Synod unanimously decided to include the two monks in the Church’s Hagiologion (catalogue of saints), according to the brief announcement it issued yesterday, granting these figures the place they deserve.

Hatzi-George the Athonite: He was unjustly expelled from Mount Athos

The son of a wealthy couple, Hatzi-George was born with the name Gabriel in 1809 in the region of Kermeira in Cappadocia. He grew up in a home where his parents generously shared their goods with those in need. His mother Maria, a deeply religious woman whose sister was a nun, often took him along when she visited her. According to numerous accounts of his life, this “ignited” in his heart the desire to become a monk, and from childhood he devoted himself to strict fasting and prayer.

Although very intelligent, he was unable to learn his letters or read at school, and as a result was scolded by both his teacher and his parents. Disheartened, he gradually withdrew for a month to caves around Kermeira, praying and making continuous prostrations since he could not even syllable out words.

As it has been written, his mother urged him to go to church and ask the Virgin Mary to help him. He went at night and knelt outside the closed church door, saying: “Grant me, Queen of Heaven, to learn my letters.” According to the accounts, the church door then opened, the Theotokos appeared, took the boy by the hand, led him to Christ’s icon and said: “My Son, grant little Gabriel to learn his letters.”

Years later he said that the Virgin told him he had learned his letters, blessed him with her hand and kissed him, then entered through the north gate of the sanctuary. The sexton who found him asked what he was doing in the church at such an hour. When the boy told him what had happened, he gave him a book to read, and Gabriel read it aloud clearly and distinctly. After this event, his parents and relatives held him in reverence, seeing that the child had experienced something divine. A few years later, in 1823, the adolescent—who was increasingly living as an ascetic—had another experience considered extraordinary.

On his way to Constantinople, where an uncle of his had converted to Islam, he lost his way while searching for hermit monks and begged Saint George to help him. The Saint appeared before him, placed him on his horse, and led him to the right road and back to his companions. Upon arriving in Constantinople, after some time he managed to persuade his uncle to return to Christianity.

He remained in the City for four years and then departed for Mount Athos. He first stayed at the Monastery of Gregoriou and later went to the area of Kavsokalyvia to find his compatriot Papa Neophytos Karamanlis. Although still a novice, the 19-year-old showed maturity beyond his years. There, in the Sketes (cells), he was tonsured a monk with the name George, and together with Papa Neophytos remained four years in the Cell of the Holy Apostles.

Hatzi-George became an Elder in 1848 at Kerassia and stood out for his gentle speech, which led young monks to obey him out of reverence rather than fear. He never took medicine, saying the best remedy was frequent Communion of Christ’s Immaculate Mysteries and frequent confession. Neither he nor the monks around him required much material food; their usual diet consisted of nuts and honey.

This “poor man of God” wore only a tunic and trousers. He listened to people and helped them overcome difficulties with his words. Yet some Russian Athonite monks envied him and systematically slandered him, falsely accusing him and eventually persuading the Holy Community of Mount Athos to expel him.

In October 1882, Hatzi-George the Athonite arrived in Constantinople, wounded in spirit and separated from his beloved spiritual children. He settled in a deserted monastery and continued living an ascetic life, receiving suffering Christians during the last years of his life. He spent his final days bedridden, in pain throughout his body—especially his legs. He reposed on December 30, 1886, and was buried at the Church of the Life-Giving Spring in Baloukli.

Tychon the Athonite: The spiritual father of Saint Paisios

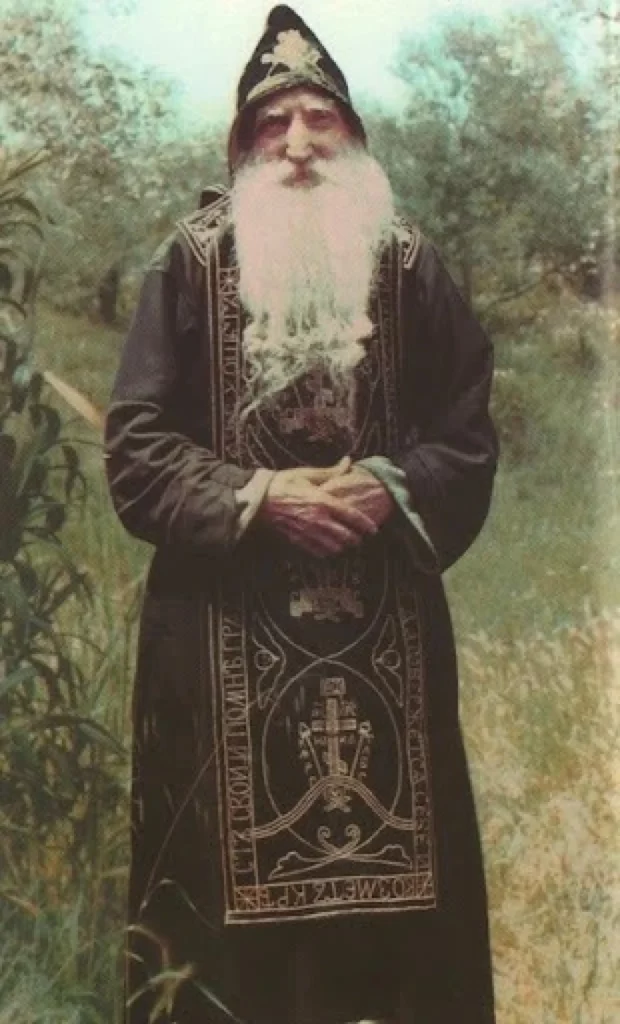

It is difficult for an ordinary person to believe that a monk once spent an entire month eating tiny pieces from a normal-sized loaf of bread. Yet this was done by Timotheos Golegkov in the world, known as Tychon the Athonite—an ascetic monk who visited hundreds of monasteries before choosing Mount Athos.

Like Hatzi-George, he felt drawn to monastic life from a young age in Nova Mikhailovska, Russia, where he was born in 1884 to parents Pavlos and Eleni. From age 17 to 20, Timotheos undertook long and endless pilgrimages to some 200 monasteries across Russia. Although he usually arrived exhausted, he rested only a few hours and avoided staying one or two days so as not to burden the monks and to continue his own ascetic struggle.

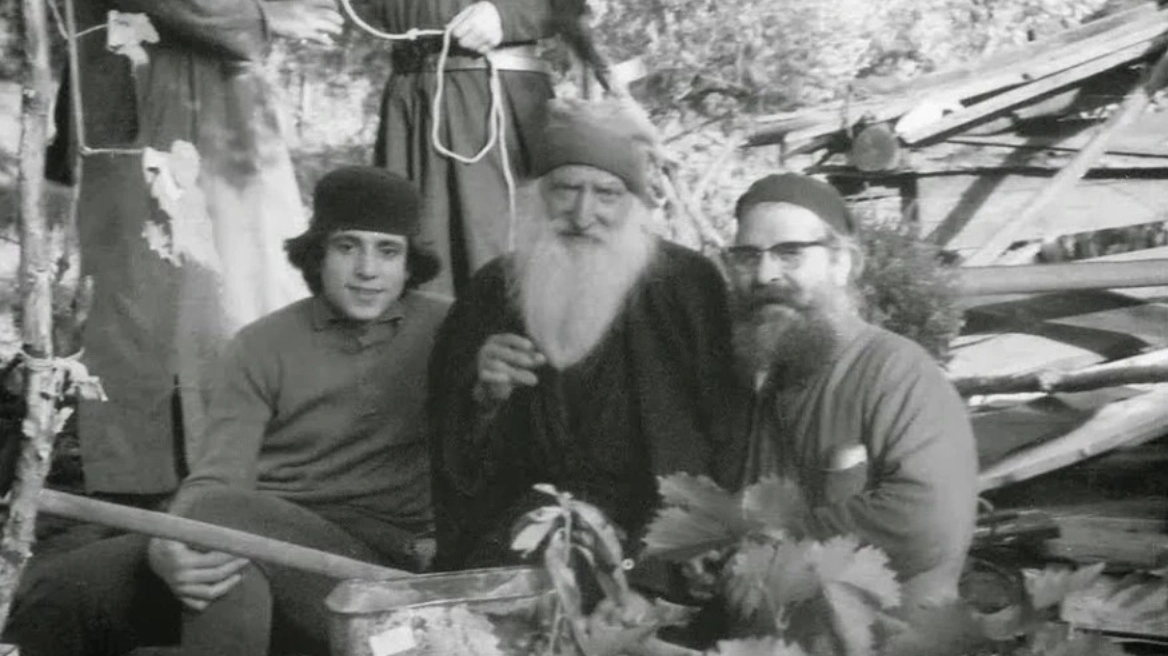

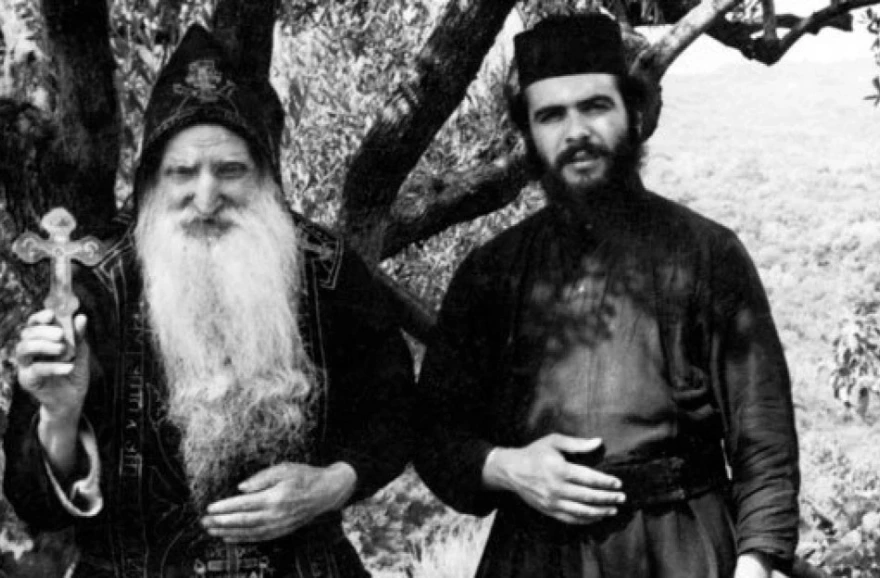

After venerating the Holy Places and the Monastery of Sinai, he arrived as an adult at Mount Athos, where he was tonsured at the Cell of Saint Nicholas Bourazeri with the name Tychon. After the first five years, desiring a higher spiritual life, he went to Karoulia for the next 15 years, lived in a cave, and ate every three days. Under the guidance of a wise elder, his entire time was devoted to prayer, reading, and prostrations.

After Karoulia he went to Kapsala, to a Stavronikita cell, with an elderly monk whom he cared for. At others’ urging, he became a priest and confessor. He built a chapel dedicated to the Exaltation of the Holy Cross and at one point kept two young monks as disciples for eight months.

“Here in the desert where we have come,” he would tell them, “we must glorify God and not sleep and eat like animals.” During the week they ate once daily, without oil.

After his simple meal, Father Tychon would walk calmly around his hut reciting prayers. When someone asked what he was doing, he would reply in five words: “The heart is beginning to warm.” Divine words came from his mouth even while he slept. When he had a visitor, the formal “banquet” consisted of olives he cut at that moment, salt, and dry bread.

He knew—or sensed—why someone had come to see him. Once, upon seeing a young man, he told him he had not come for him but to check whether the area had wild boars.

When he celebrated the Divine Liturgy in a dark church, his eyes shone with light. He always read the Gospel with sobs and kept Holy Bread reserved. He communed daily anyone who wished and made the climb to his hut. Elder Gerontios once saw him lifted above the ground. Saint Paisios had him as his spiritual father and has said that during one Liturgy his voice disappeared for five hours, evidently because he had entered another spiritual state.

He made about three thousand prostrations daily, and from long hours of standing his legs were swollen—something that did not trouble him at all. An elder from Karyes said that Father Tychon was very simple and lived in his own world, and although he fasted, he was physically robust. “When he came to our cell and we set food before him,” he said, “he would eat only two spoonfuls, as a blessing. Now there is no one like him…”

He fell asleep in the Lord on September 10, 1968, having previously seen in a vision the Virgin Mary together with Saint Sergius and Saint Seraphim, who told him that after the feast of the Nativity of the Theotokos they would come to take him.

At his side was his disciple, Elder Paisios, who cared for him in his old age, buried him, succeeded him in the hut—and became a saint before his spiritual father.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions